In discussions about foliar fertilization, the question often arises whether this cultivation measure makes sense. After all, the absorption of minerals is the work of the roots. That is correct, but the magazine also makes a significant contribution, as scientific research confirms time and time again. The leaves of most plant species are even very suitable for the absorption of water, amino acids and minerals. The range may be wider than you think. Nutritional intake via the leaves is actually an indispensable backup system.

Help from above

Help from above

Foliar fertilization is also a natural phenomenon that has existed since plants grew on earth. An example of this is found in dark rainforests. In these forests, low-growing plants do not receive direct sunlight. As a result, photosynthesis is at a low level and they produce few sugars for growth and release to the roots.

With a low photosynthesis level, fewer sugars enter the soil and the plant can absorb little food. Yet they survive by actively absorbing amino acids, minerals and even humus fractions through their leaves. This natural foliar fertilizer comes from the upper layer of the forest, where fine (organic) dust particles, dead insects, bird droppings, algae and mosses collect. The nutrients released from this fall on the underlying plants as foliar fertilizer when it rains. Because most cultivated crops originally grow in forests, they can usually process foliar fertilization very well.

Three mechanisms for absorption

There are basically three ways in which minerals and amino acids can be absorbed by the leaf: via the leaf hairs (trichomes), via the wax layer on the leaf (cuticle) and by absorption and release via cells (endocytosis).

Most plant species have many more stomata on the underside of the leaf than on the top. That is a signal that they are not fond of water. The stomata are well equipped for respiration and evaporation, but they are not really suitable as absorption organs.

Trichomes (leaf hairs) are single-celled outgrowths of the epidermis. Positively charged minerals and amino acids are usually well absorbed through these bulges. The negatively charged plants can also draw in positively charged leaf fertilizers through their wax layer (cuticle).

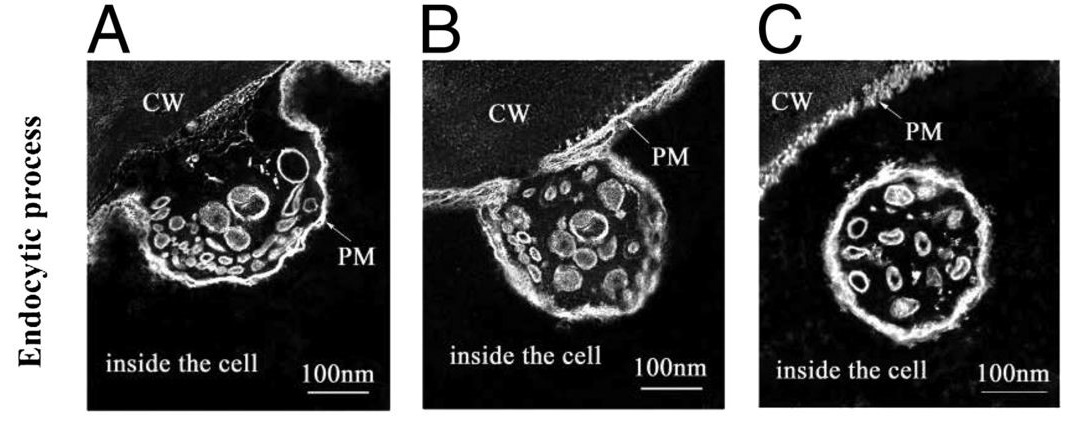

During endocytosis (uptake and release via cells), minerals on the leaf are enclosed by an epidermis. The inclusion is then released in the plant and is transported to so-called storage cells (sink cells), which absorb the minerals and store them for later use. Figure 1 shows the first part of this process. The principle actually works the same as nicotine patches, which slowly release nicotine into the body through the skin.

Figure 1. Uptake of nutrients by leaves via endocytosis.

Nutrient supply too narrow

For many decades, people around the world have been working with the 17 known macro- and micro-elements that plants need according to current fertilization theory. Supplemented with oxygen, water and CO2, there are 21 substances. Supported by more recent research, it is becoming clear that plants absorb much more from the soil than previously thought. And that people and animals also need more elements for healthy functioning.

This also includes a large number of rare earth elements. These are elements that occur in very small quantities in almost every soil type. Research into the use of very small amounts of the elements lanthanum and cerium, for example, shows yield improvements in several arable crops.

New insights

All things considered, it is now known that plants need more than the 17 basic elements to grow healthily. It is also likely that rare earth elements are no longer or insufficiently present in old cultivated soils after many years of harvesting and disposal. This soil impoverishment can also explain the declining nutritional value of agricultural and horticultural crops over the past 40 years.

Due to this advancing insight, both researchers and farmers have started to enrich old agricultural land with rock dust. This contains trace elements that cannot be found in any classical fertilizer analysis. Much positive experience has already been gained with this, especially in Germany, Switzerland and Austria.

Fast and practical with PHC foliar fertilizers

Fast and practical with PHC foliar fertilizers

Much research is still needed to uncover all the facts and to rule out uncertainties. Growers can wait for that, but they can also pre-sort. This can be done, for example, by using a combination of rock dust and beneficial soil bacteria. A faster way to experience that plants appreciate a wider range of minerals is foliar fertilization. A good foliar fertilizer does not contain too much nitrogen, many amino acids and a variety of elements that are only found in organic fertilizers.

Plants quickly show whether foliar fertilization is functional or not. For growers it is a fast and practical way to control plant growth as needed and better guide fruit setting and ripening.

view all PHC foliar fertilizers

- Nederlands

- English

- Deutsch

- Francais